| Tutankhamun | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tutankhaten, Tutankhamon,[1] possibly Nibhurrereya (as referenced in the Amarna letters) | ||

| Pharaoh | ||

| Reign | c. 1332–1323 BC, New Kingdom(18th Dynasty) | |

| Predecessor | Neferneferuaten | |

| Successor | Ay (granduncle/grandfather-in-law) | |

| ||

| Consort | Ankhesenamun (half-sister and cousin) | |

| Children | Two stillborn daughters | |

| Father | KV55 mummy [2] identified as probably Akhenaten | |

| Mother | The Younger Lady | |

| Born | c. 1341 BC | |

| Died | c. 1323 BC (aged c. 18 or 19) | |

| Burial | KV62 | |

The Tutankhamun Exhibition will go on display at the Saatchi Gallery in London from 2nd November 2019 to 3rd May 2020. This is the final time these extraordinary treasures will appear in London, and the largest exhibition to ever tour, celebrating the centenary since the discovery of the tomb. Apr 26, 2019- Tutankhamun 'Living Image of Amun' (alt. Spelled with Tutenkh-, -amen, -amon, popularly referred to as King Tut) Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled ca. 1332 BC – 1323 BC). See more ideas about Egyptian art, Ancient artifacts and Ancient Egypt.

Tutankhamun (/ˌtuːtənkɑːˈmuːn/;[3] alternatively spelled with Tutenkh-, -amen, [a]-amon; c. 1341 – c. 1323 BC) was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled c. 1332–1323 BC in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. He has, since the discovery of his intact tomb, been referred to colloquially as King Tut.

His original name, Tutankhaten, means 'Living Image of Aten', while Tutankhamun means 'Living Image of Amun'. In hieroglyphs, the name Tutankhamun was typically written Amen-tut-ankh, because of a scribal custom that placed a divine name at the beginning of a phrase to show appropriate reverence.[4] He is possibly also the Nibhurrereya of the Amarna letters, and likely the 18th dynasty king Rathotis who, according to Manetho, an ancient historian, had reigned for nine years—a figure that conforms with Flavius Josephus's version of Manetho's Epitome.[5]

The 1922 discovery by Howard Carter of Tutankhamun's nearly intact tomb, funded by Lord Carnarvon,[6][7] received worldwide press coverage. It sparked a renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun's mask, now in the Egyptian Museum, remains a popular symbol. In February 2010, genetic testing confirmed that he was the son of the mummy found in the tomb KV55, believed by some to be Akhenaten. His mother was his father's sister and wife, whose name is unknown but whose remains are positively identified as 'The Younger Lady' mummy found in KV35.[8] The deaths of a few involved in the discovery of Tutankhamun's mummy have been popularly attributed to the curse of the pharaohs.[9]

- 1Life

- 2Tomb

- 7References

Life

Tutankhamun was most likely the son of Akhenaten (formerly Amenhotep IV) and one of Akhenaten's sisters,[2] or possibly one of his cousins.[10] As a prince, he was known as Tutankhaten.[11] He ascended to the throne in 1333 BC, at the age of nine or ten, taking the throne name Nebkheperure.[12] His wet nurse was a woman called Maia, known from her tomb at Saqqara.[13] His teacher was most likely Sennedjem.

When he became king, he married his half-sister, Ankhesenpaaten, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun. They had two daughters, neither of whom survived infancy.[8]Computed tomography studies released in 2011 revealed that one daughter was born prematurely at 5–6 months of pregnancy and the other at full-term, 9 months.[14] The daughter born at 9 months gestation had spina bifida, scoliosis, and Sprengel's deformity (a condition affecting the placement of the scapula).[15]

Reign

Tutankhamun was nine years old when he became Pharaoh, and he reigned for about ten years.[16] Tutankhamun is historically significant because his reign was near the apogee of Egypt as a world power and because he rejected the radical religious innovations introduced by his predecessor and father, Akhenaten.[17] Secondly, his tomb in the Valley of the Kings was discovered by Carter almost completely intact—the most complete ancient Egyptian royal tomb found. As Tutankhamun began his reign so young, his vizier and eventual successor, Ay, was probably making most of the important political decisions during Tutankhamun's reign.

Kings were venerated after their deaths through mortuary cults and associated temples. Tutankhamun was one of the few kings worshiped in this manner during his lifetime.[18] A stela discovered at Karnak and dedicated to Amun-Ra and Tutankhamun indicates that the king could be appealed to in his deified state for forgiveness and to free the petitioner from an ailment caused by sin. Temples of his cult were built as far away as in Kawa and Faras in Nubia. The title of the sister of the Viceroy of Kush included a reference to the deified king, indicative of the universality of his cult.[19]

The country was economically weak and in turmoil following the reign of Akhenaten. Diplomatic relations with other kingdoms had been neglected, and Tutankhamun sought to restore them, in particular with the Mitanni. Evidence of his success is suggested by the gifts from various countries found in his tomb. Despite his efforts for improved relations, battles with Nubians and Asiatics were recorded in his mortuary temple at Thebes. His tomb contained body armor, folding stools appropriate for military campaigns, and bows, and he was trained in archery.[20] However, given his youth and physical disabilities, which seemed to require the use of a cane in order to walk, most historians speculate that he did not personally take part in these battles.[8][21][22]

As part of his restoration, the king initiated building projects, in particular at Karnak in Thebes, where he dedicated a temple to Amun. Many monuments were erected, and an inscription on his tomb door declares the king had 'spent his life in fashioning the images of the gods'. The traditional festivals were now celebrated again, including those related to the Apis Bull, Horemakhet, and Opet. His restoration stela says:

The temples of the gods and goddesses .. were in ruins. Their shrines were deserted and overgrown. Their sanctuaries were as non-existent and their courts were used as roads .. the gods turned their backs upon this land .. If anyone made a prayer to a god for advice he would never respond.[23]

Given his age, the king probably had very powerful advisers, presumably including General Horemheb (Grand Vizier Ay's possible son in law and successor) and Grand Vizier Ay (who succeeded Tutankhamun). Horemheb records that the king appointed him 'lord of the land' as hereditary prince to maintain law. He also noted his ability to calm the young king when his temper flared.[24]

In his third regnal year, under the influence of his advisors, Tutankhamun reversed several changes made during his father's reign. He ended the worship of the god Aten and restored the god Amun to supremacy. The ban on the cult of Amun was lifted and traditional privileges were restored to its priesthood. The capital was moved back to Thebes and the city of Akhetaten abandoned.[25] This is when he changed his name to Tutankhamun, 'Living image of Amun', reinforcing the restoration of Amun.

Health and appearance

Tutankhamun was slight of build, and roughly 167 cm (5 ft 6 in) tall.[26][27] He had large front incisors and an overbite characteristic of the Thutmosid royal line to which he belonged. Between September 2007 and October 2009, various mummies were subjected to detailed anthropological, radiological, and genetic studies as part of the King Tutankhamun Family Project. The research showed that Tutankhamun also had 'a slightly cleft palate'[28] and possibly a mild case of scoliosis, a medical condition in which the spine deviates to the side from the normal position. It was posited in the 2002 documentary 'Assassination of King Tut' for the Discovery Channel that he suffered from Klippel-Feil syndrome, but subsequent analysis excluded this as an acceptable diagnosis.[29] Examination of Tutankhamun's body has also revealed deformations in his left foot, caused by necrosis of bone tissue. The affliction may have forced Tutankhamun to walk with the use of a cane, many of which were found in his tomb.[30] In DNA tests of Tutankhamun's mummy, scientists found DNA from the mosquito-borne parasites that cause malaria. This is currently the oldest known genetic proof of the disease. More than one strain of the malaria parasite was found, indicating that Tutankhamun contracted multiple malarial infections.[30]

Genealogy

In 2008, a team began DNA research on Tutankhamun and the mummified remains of other members of his family. The results indicated that his father was Akhenaten, and that his mother was not one of Akhenaten's known wives but one of his father's five sisters. The techniques used in the study, however, have been questioned.[31][32] The team reported it was over 99.99 percent certain that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.[33] The young king's mother was found through the DNA testing of a mummy designated as 'The Younger Lady' (KV35YL), which was found lying beside Queen Tiye in the alcove of KV35. Her DNA proved that, like his father, she was a child of Amenhotep III and Tiye; thus, Tutankhamun's parents were brother and sister.[33] Queen Tiye held much political influence at court and acted as an adviser to her son after the death of her husband. Some geneticists dispute these findings, however, and 'complain that the team used inappropriate analysis techniques.'[34]

While the data are still incomplete, the study suggests that one of the mummified fetuses found in Tutankhamun's tomb is the daughter of Tutankhamun himself, and the other fetus is probably his child as well. So far, only partial data for the two female mummies from KV21 has been obtained.[33] One of them, KV21A, may be the infants' mother, and, thus, Tutankhamun's wife, Ankhesenamun. It is known from history that she was the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and thus likely to be her husband's half-sister. One consequence of inbreeding can be children whose genetic defects do not allow them to be brought to term.[citation needed]

Death

There are no surviving records of Tutankhamun's death. The cause of his death has been the subject of considerable debate and major studies have been conducted to establish it. A CT scan taken in 2005 showed that he had suffered a compound left leg fracture[35] shortly before his death, and that the leg had become infected. DNA analysis conducted in 2010 showed the presence of malaria in his system, leading to the belief that a combination of malaria and Köhler disease II led to his death.[36]

Research conducted in 2005 by archaeologists, radiologists, and geneticists, who performed CT scans on the mummy, found that he was not killed by a blow to the head, as previously thought.[33] New CT images discovered congenital flaws, which are more common among the children of incest. Siblings are more likely to pass on twin copies of deleteriousalleles, which is why children of incest more commonly manifest genetic defects.[37] It is suspected he also had a partially cleft palate, another congenital defect.[33]

Various other diseases, invoked as possible explanations to his early demise, included Marfan syndrome, Wilson-Turner X-linked mental retardation syndrome, Fröhlich syndrome (adiposogenital dystrophy), Klinefelter syndrome, androgen insensitivity syndrome, aromatase excess syndrome in conjunction with sagittal craniosynostosis syndrome, Antley–Bixler syndrome or one of its variants,[38] and temporal lobe epilepsy.[39]

A research team conducted further CT scans, STR analysis have rejected the hypothesis of gynecomastia and craniosynostoses (e.g., Antley-Bixler syndrome) or Marfan syndrome, but an accumulation of malformations in Tutankhamun's family was evident. Several pathologies including Köhler disease II were diagnosed in Tutankhamun; none alone would have caused death. Genetic testing for STEVOR, AMA1, or MSP1 genes specific for Plasmodium falciparum revealed indications of malaria tropica in 4 mummies, including Tutankhamun's.[8] However, their exact contribution to the causality of his death still is highly debated.

As stated above, the team discovered DNA from several strains of a parasite, proving that he was repeatedly infected with the most severe strain of malaria, several times in his short life. Malaria can cause a fatal immune response in the body or trigger circulatory shock which can also lead to death. If Tutankhamun did suffer from a bone disease which was crippling, it may not have been fatal. 'Perhaps he struggled against other [congenital flaws] until a severe bout of malaria or a leg broken in an accident added one strain too many to a body that could no longer carry the load', wrote Zahi Hawass, archeologist and head of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquity involved in the research.[40]

A review of the medical findings to date found that he suffered from mild kyphoscoliosis, pes planus (flat feet), hypophalangism of the right foot, bone necrosis of the second and third metatarsal bones of the left foot, malaria, and a complex bone fracture of the right knee, which occurred shortly before his death.[41]

Several experts argue that Ancient Egyptian DNA does not always survive to a level that's easily retrievable and question the validity and reliability of the genetic data that is collected from Ancient Egyptian sources. One expert argues that most of the injuries inflicted upon Tutankhamun had to have happened prior and during mummification, due to a test he performed upon dried bones that crumbled when he attempted to cut them, ruling out that Tutankhamun's chest had been cut by Carter or anyone after him.[42] Several experts support the notion that King Tutankhamun died as the result of an accident, whether it be from hunting or chariot crash. Some believe that Tutankhamun died suddenly away from home and had to be rushed back for mummification. Dr. Jo Marchant, a historian, admits in her book 'The Shadow King' that she too, personally believes that Pharaoh Tutankhamun died as the result of an accident, stating that all the evidence suggests that Tutankhamn had been a young man who must have taken one risk too many and ended his life early, also stating that the accident theory supports all of the oddities surrounding Tutankhamun's mummification and burial; she likewise points out that many scientists agree that while Ashraj Selim and his team are wonderful and skilled radiologists, they are not experienced in examining ancient mummies, and therefore cannot easily diagnose an ancient mummy.[42]

Tomb

Tutankhamun was buried in a tomb that was unusually small considering his status. His death may have occurred unexpectedly, before the completion of a grander royal tomb, causing his mummy to be buried in a tomb intended for someone else. This would preserve the observance of the customary 70 days between death and burial.[43]

In 1915, George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, the financial backer of the search for and the excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb in the Valley of the Kings, employed English archaeologist Howard Carter to explore it. After a systematic search, Carter discovered the actual tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) in November 1922,[44] and unsealed the burial chamber on 16 February 1923.[45]

On 4 November 2007, 85 years to the day after Carter's discovery, Tutankhamun's mummy was placed on display in his underground tomb at Luxor, when the linen-wrapped mummy was removed from its golden sarcophagus to a climate-controlled glass box. The case was designed to prevent the heightened rate of decomposition caused by the humidity and warmth from tourists visiting the tomb.[46]

His tomb was robbed at least twice in antiquity, but based on the items taken (including perishable oils and perfumes) and the evidence of restoration of the tomb after the intrusions, these robberies likely took place within several months at most of the initial burial. The location of the tomb was lost because it had come to be buried by debris from subsequent tombs, and worker's houses were built over the tomb entrance. Tutankhamun's tomb was unaffected when the Valley of the Kings burial sites were systematically dismantled at the end of the 20th Dynasty.[citation needed]

There were 5,398 items found in the tomb, including a solid gold coffin, face mask, thrones, archery bows, trumpets, a lotus chalice, food, wine, sandals, and fresh linen underwear. Howard Carter took 10 years to catalog the items.[47] Recent analysis suggests a dagger recovered from the tomb had an iron blade made from a meteorite; study of artifacts of the time including other artifacts from Tutankhamun's tomb could provide valuable insights into metalworking technologies around the Mediterranean at the time.[48][49][50][51]

According to Nicholas Reeves, almost 80% of Tutankhamun's burial equipment originated from the female pharaoh Neferneferuaten's funerary goods, including the Mask of Tutankhamun[52][53]In 2015, Reeves published evidence showing that an earlier cartouche on Tutankhamun's famous gold mask read 'Ankhkheperure mery-Neferkheperure' (Ankhkheperure beloved of Akhenaten); therefore, the mask was originally made for Nefertiti, Akhenaten's chief queen, who used the royal name Ankhkheperure when she most likely assumed the throne after her husband's death.[54]

This development implies that either Neferneferuaten (likely Nefertiti if she assumed the throne after Akhenaten's death) was deposed in a struggle for power, possibly deprived of a royal burial—and buried as a Queen—or that she was buried with a different set of king's funerary equipment—possibly Akhenaten's own funerary equipment by Tutankhamun's officials since Tutankhamun succeeded her as king.[55] Neferneferuaten was likely succeeded by Tutankhamun based on the presence of her funerary goods in his tomb.

In January 2019, it was announced that the tomb would re-open to visitors after nine years of restoration.[56]

Curse

For many years, rumors of a 'curse of the pharaohs' (probably fueled by newspapers seeking sales at the time of the discovery)[57] persisted, emphasizing the early death of some of those who had entered the tomb. The most prominent was George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon who died on 5 April 1923, 5 months after the discovery of the first step leading down to the tomb on 4 November 1922.

A study of documents and academic sources led The Lancet to conclude that Carnarvon's death had nothing to do with Tutankhamun's tomb, regardless of whether because of a curse or exposure to toxic fungi (mycotoxins).[58] The cause of Carnarvon's death was pneumonia supervening on [facial] erysipelas (a streptococcal infection of the skin and underlying soft tissue). Pneumonia was thought to be only one of various complications, arising from the progressively invasive infection, that eventually resulted in multiorgan failure'.[59] The Earl had been 'prone to frequent and severe lung infections' according to The Lancet and there had been a 'general belief .. that one acute attack of bronchitis could have killed him. In such a debilitated state, the Earl's immune system was easily overwhelmed by erysipelas'.[58]

A study showed that of the 58 people who were present when the tomb and sarcophagus were opened, only eight died within a dozen years. All the others were still alive, including Howard Carter,[60] who died of lymphoma in 1939 at the age of 64.[61][62] The last survivors included Lady Evelyn Herbert, Lord Carnarvon's daughter who was among the first people to enter the tomb after its discovery in November 1922, who lived for a further 57 years and died in 1980,[63] and American archaeologist J.O. Kinnaman who died in 1961, 39 years after the event.[64]

Legacy

If Tutankhamun is the world's best known pharaoh, it is largely because his tomb is among the best preserved, and his image and associated artifacts the most exhibited. As Jon Manchip White writes, in his foreword to the 1977 edition of Carter's The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, 'The pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt's Pharaohs has become in death the most renowned'.

The discoveries in the tomb were prominent news in the 1920s. Tutankhamen came to be called by a modern neologism, 'King Tut'. Ancient Egyptian references became common in popular culture, including Tin Pan Alley songs; the most popular of the latter was 'Old King Tut' by Harry Von Tilzer from 1923, which was recorded by such prominent artists of the time as Jones & Hare and Sophie Tucker. 'King Tut' became the name of products, businesses, and the pet dog of U.S. President Herbert Hoover.

Relics from Tutankhamun's tomb are among the most traveled artifacts in the world. They have been to many countries, but probably the best-known exhibition tour was The Treasures of Tutankhamun tour, which ran from 1972 to 1979. This exhibition was first shown in London at the British Museum from 30 March until 30 September 1972. More than 1.6 million visitors saw the exhibition, some queuing for up to eight hours. It remains the most popular exhibition in the Museum's history.[65] The exhibition moved on to many other countries, including the United States, Soviet Union, Japan, France, Canada, and West Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art organized the U.S. exhibition, which ran from 17 November 1976 through 15 April 1979. More than eight million attended.

In 2005, Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, in partnership with Arts and Exhibitions International and the National Geographic Society, launched a tour of Tutankhamun treasures and other 18th Dynasty funerary objects, this time called Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. It featured the same exhibits as Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter in a slightly different format. It was expected to draw more than three million people.[66]

The exhibition started in Los Angeles, then moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Chicago and Philadelphia. The exhibition then moved to London[67] before finally returning to Egypt in August 2008. An encore of the exhibition in the United States ran at the Dallas Museum of Art from October 2008 to May 2009.[68] The tour continued to other U.S. cities.[69] After Dallas the exhibition moved to the de Young Museum in San Francisco, followed by the Discovery Times Square Exposition in New York City.[70]

In 2011, the exhibition visited Australia for the first time, opening at the Melbourne Museum in April for its only Australian stop before Egypt's treasures returned to Cairo in December 2011.[71]

The exhibition included 80 exhibits from the reigns of Tutankhamun's immediate predecessors in the 18th dynasty, such as Hatshepsut, whose trade policies greatly increased the wealth of that dynasty and enabled the lavish wealth of Tutankhamun's burial artifacts, as well as 50 from Tutankhamun's tomb. The exhibition does not include the gold mask that was a feature of the 1972–1979 tour, as the Egyptian government has decided that damage which occurred to previous artifacts on tours precludes this one from joining them.[72]

Names

| Horus name | 𓅃𓃒𓂡𓏏𓅱𓏏𓄟𓋴𓏏𓅱𓏪𓊁 Kanakht Tutmesut The strong bull, pleasing of birth | |||||||||||||||

| Nebti name | 𓅒𓄤𓉔𓊪𓅱𓇩𓏪𓋴𓎼𓂋𓎛𓂝𓇿𓇿𓈅𓈅𓅨𓉥𓉐𓏤𓇋𓏠𓈖𓎟𓂋𓇥𓂋𓀯 Neferhepusegerehtawy Werahamun Nebrdjer One of perfect laws, who pacifies the two lands; Great of the palace of Amun; Lord of all[73] | |||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus name | 𓅉𓍞𓈍𓏥𓊃𓊵𓏏𓊪𓊹𓊹𓊹𓋾𓈎𓏛𓁦𓋴𓊵𓏏𓊪𓊹𓊹𓊹𓅱𓍿𓊃𓍞𓈍𓏥𓇋𓏏𓆑𓀯𓆑𓁛𓍞𓈍𓏥𓋭𓊃𓇾𓇾𓅓 Wetjeskhausehetepnetjeru Heqamaatsehetepnetjeru Wetjeskhauitefre Wetjeskhautjestawyim Who wears crowns and pleases the gods; Ruler of Truth, who pleases the gods; Who wears the crowns of his father, Re; Who wears crowns, and binds the two lands therein | |||||||||||||||

| Prenomen | 𓇓𓆤 𓍹𓇳𓆣𓏥𓎟𓍺 Nebkheperure Lord of the forms of Re | |||||||||||||||

| Son of Re | 𓅭𓇳 𓍹𓇋𓏠𓈖𓏏𓅱𓏏𓋹𓋾𓉺𓇗𓍺 Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema Living Image of Amun, ruler of Upper Heliopolis |

At the reintroduction of traditional religious practice, his name changed. It is transliterated as twt-ꜥnḫ-ỉmn ḥqꜣ-ỉwnw-šmꜥ, and according to modern Egyptological convention is written Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema, meaning 'Living image of Amun, ruler of Upper Heliopolis'. On his ascension to the throne, Tutankhamun took a prenomen. This is transliterated as nb-ḫprw-rꜥ, and, again, according to modern Egyptological convention is written Nebkheperure, meaning 'Lord of the forms of Re'. The name Nibhurrereya (𒉌𒅁𒄷𒊑𒊑𒅀) in the Amarna letters may be closer to how his prenomen was actually pronounced.

Ancestry

| Amenhotep II | Tiaa | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thutmose IV | Mutemwiya | Yuya | Tjuyu | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Amenhotep III | Tiye | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| KV55, possibly Akhenaten | The Younger Lady | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tutankhamun |

See also

References

Footnotes

Citations

- ^Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 128. ISBN978-0-500-28628-9.

- ^ abHawass, Zahi; et al. (17 February 2010). 'Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family'. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (7): 640–641. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ ab'Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen'. Collins English Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^Zauzich, Karl-Theodor (1992). Hieroglyphs Without Mystery. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN978-0-292-79804-5.

- ^'Manetho's King List'.

- ^'The Egyptian Exhibition at Highclere Castle'. Archived from the original on 3 September 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^Hawass, Zahi A. The golden age of Tutankhamun: divine might and splendor in the New Kingdom. American Univ in Cairo Press, 2004.

- ^ abcdHawass, Zahi; et al. (17 February 2010). 'Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family'. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (7): 638–647. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121. PMID20159872. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^'Digging up trouble: beware the curse of King Tutankhamun'. The Guardian.

- ^Powell, Alvin (12 February 2013). 'A different take on Tut'. Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^van Dijk, Jacobus. 'The Death of Meketaten'(PDF). p. 7. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ^'Classroom TUTorials: The Many Names of King Tutankhamun'(PDF). Michael C. Carlos Museum. Archived from the original(PDF) on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^'Egypt Update: Rare Tomb May Have Been Destroyed'. Science Mag. 4 February 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^Hawass, Zahi and Saleem, Sahar N. 'Mummified daughters of King Tutankhamun: Archaeological and CT studies.' The American Journal of Roentgenology 2011. Vol 197, No. 5, pp. W829–836.

- ^Kozma, C. (2008). 'Skeletal dysplasia in ancient Egypt'. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 146A (23): 3104–12. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32501. PMID19006207.

- ^Redford, Donald B., PhD; McCauley, Marissa. 'How were the Egyptian pyramids built?'. Research. The Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^Aude Gros de Beler, Tutankhamun, foreword Aly Maher Sayed, Molière, ISBN2-84790-210-4

- ^Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology, Editor Donald B. Redford, p. 85, Berkley, ISBN0-425-19096-X

- ^Booth 2007, p. 120.

- ^Gilbert, Holt & Hudson 1976, pp. 28–9.

- ^Booth 2007, pp. 129–30.

- ^Channel 5 (UK), 24 March 2018: King Tut's Treasure Secrets, part 1 of 3

- ^Hart, George (1990). Egyptian Myths. University of Texas Press. p. 47. ISBN978-0-292-72076-3.

- ^Booth 2007, pp. 86–87.

- ^Erik Hornung, Akhenaten and the Religion of Light, Translated by David Lorton, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBN0-8014-8725-0.

- ^Hawass, Zahi; Saleem, Sahar N. (2016). Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. New York: American University in Cairo Press. p. 94. ISBN978-977-416-673-0.

- ^Carter, Howard; Derry, Douglas E. (1927). The Tomb of Tutankhamen. Cassel and Company, LTD. p. 157.

- ^Handwerk, Brian (8 March 2005). 'King Tut Not Murdered Violently, CT Scans Show'. National Geographic News. p. 2. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^Boyer, Richard S.; Rodin, Ernst A.; Grey, Todd C.; Connolly, R. C. (June 2003). 'The Skull and Cervical Spine Radiographs of Tutankhamun: A Critical Appraisal'(PDF). American Journal of Neuroradiology. 24 (6): 1146. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ ab'King Tut Was Disabled, Malarial, and Inbred, DNA Shows'. nationalgeographic.com. 17 February 2010.

- ^Nature 472, 404–6 (2011); Published online 27 April 2011; Original link

- ^NewScientist.com; January 2011;Royal Rumpus over King Tutankhamun's Ancestry

- ^ abcdeHawass, Zahi (September 2010). 'King Tut's Family Secrets'. National Geographic. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^'DNA experts disagree over Tutankhamun's ancestry'. Archaeology News Network. 22 January 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^Hawass, Zahi. 'Tutankhamon, segreti di famiglia'. National Geographic (in Italian). Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^Roberts, Michelle (16 February 2010). ''Malaria' killed King Tutankhamun'. BBC News. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^Bates, Claire (20 February 2010). 'Unmasked: The real faces of the crippled King Tutankhamun (who walked with a cane) and his incestuous parents'. Daily Mail. London.

- ^Markel, H. (17 February 2010). 'King Tutankhamun, modern medical science, and the expanding boundaries of historical inquiry'. JAMA. 303 (7): 667–668. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.153. PMID20159878.(subscription required)

- ^Rosenbaum, Matthew (14 September 2012). 'Mystery of King Tut's death solved?'. ABC News. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^Hawass, Zahi (1 September 2010). 'King Tut's Family Secrets'. National Geographic Magazine. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^Hussein, Kais; Matin, Ekatrina; Nerlich, Andreas G. (2013). 'Paleopathology of the juvenile Pharaoh Tutankhamun—90th anniversary of discovery'. Virchows Archiv. 463 (3): 475–479. doi:10.1007/s00428-013-1441-1. PMID23812343.

- ^ abCite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^'The Golden Age of Tutankhamun: Divine Might and Splendour in the New Kingdom', Zahi Hawass, p. 61, American University in Cairo Press, 2004, ISBN977-424-836-8

- ^Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 81.

- ^'Howard Carter's diaries (1 January to 31 May 1923)'. Archived from the original on 7 April 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- ^Michael McCarthy (5 October 2007). '3,000 years old: the face of Tutankhaten'. The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 5 November 2007.

- ^Williams, A. R.; 24, National Geographic PUBLISHED November. 'King Tut: The Teen Whose Death Rocked Egypt'. National Geographic News. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^Dagger in Tutankhamun's tomb was made with iron from a meteoriteThe Guardian

- ^King Tutankhamun buried with dagger made of space iron, study finds, ABC News Online, 2 June 2016

- ^Comelli, Daniela; d'Orazio, Massimo; Folco, Luigi; et al. (2016). 'The meteoritic origin of Tutankhamun's iron dagger blade'. Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 51 (7): 1301. Bibcode:2016M&PS..51.1301C. doi:10.1111/maps.12664.'Early View (Online Version of Record published before inclusion in a printed issue)'.

- ^Walsh, Declan (2 June 2016). 'King Tut's Dagger Made of 'Iron From the Sky,' Researchers Say'. The New York Times. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^Nicholas Reeves Tutankhamun's Mask Reconsidered BES 19 (2014), pp. 511–22

- ^Peter Hessler, Inspection of King Tut's Tomb Reveals Hints of Hidden Chambers National Geographic, September 28, 2015

- ^Nicholas Reeves, The Gold Mask of Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten, Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, Vol.7 No.4, (December 2015) pp. 77–9 & click download this PDF file

- ^Nicholas Reeves,Tutankhamun's Mask Reconsidered BES 19 (2014), pp. 523–24

- ^https://plus.google.com/+travelandleisure/posts. 'King Tut's Tomb Is Reopening to Visitors After 9 Years of Dazzling Restoration Work – Take a Look Inside'. Travel + Leisure. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^Hankey, Julie (2007). A Passion for Egypt: Arthur Weigall, Tutankhamun and the 'Curse of the Pharaohs'. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 3–5. ISBN978-1-84511-435-0.

- ^ ab'The death of Lord Carnarvon'.

- ^Cox, A. M. 'The death of Lord Carnarvon'. The Lancet, 7 June 2003. [sic]

- ^Gordan, Stuart (1995). The Book of Spells, Hexes, and Curses. Carol Publishing Group. pp. New York, New York. ISBN978-08065-1675-2.

- ^David Vernon in Skeptical – a Handbook of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, ed. Donald Laycock, David Vernon, Colin Groves, Simon Brown, Imagecraft, Canberra, 1989, ISBN0-7316-5794-2, p. 25.

- ^'北京赛车pk10 pk10开奖直播 北京赛车pk10开奖结果历史记录 – pk10直播网'. www.touregypt.net.

- ^Bill Price. (21 January 2009). Tutankhamun, Egypt's Most Famous Pharaoh. p. 138. Published Pocket Essentials, Hertfordshire. 2007. ISBN9781842432402.

- ^'Death Claims Noted Biblical Archaeologist', Lodi News-Sentinel, 8 September 1961, Retrieved 9 May 2014 [1]

- ^'Record visitor figures'. British Museum. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^'King Tut exhibition. Tutankhamun & the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. Treasures from the Valley of the Kings'. Arts and Exhibitions International. Archived from the original on 2 December 2005. Retrieved 5 August 2006.

- ^Bone, James (13 October 2007). 'Return of the King'. The Times. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011.

- ^'Dallas Museum of Art Website'. Dallasmuseumofart.org. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^Associated Press, 'Tut Exhibit to Return to US Next Year' Archived 26 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^'Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs King Tut Returns to San Francisco, June 27, 2009 – March 28, 2010'. Famsf.org. Archived from the original on 20 January 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^Melbourne Museum's Tutenkhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaoh's Official SiteArchived 1 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^Jenny Booth (6 January 2005). 'CT scan may solve Tutankhamun death riddle'. The Times. London.

- ^'Digital Egypt for Universities: Tutankhamun'. University College London. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 5 August 2006.

Sources

- Booth, Charlotte (2007). The Boy Behind the Mask: Meeting the Real Tutankhamun. Oneworld. ISBN978-1-85168-544-8.

- Gilbert, Katherine Stoddert; Holt, Joan K.; Hudson, Sara, eds. (1976). Treasures of Tutankhamun. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN978-0-87099-156-1.

- Reeves, C. Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. London: Thames & Hudson, 1 November 1990, ISBN0-500-05058-9 (hardcover)/ISBN0-500-27810-5 (paperback) Fully covers the complete contents of his tomb.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings. London: Thames and Hudson.

Further reading

- Andritsos, John. Social Studies of Ancient Egypt: Tutankhamun. Australia 2006.

- Brier, Bob. The Murder of Tutankhamun: A True Story. Putnam Adult, 13 April 1998, ISBN0-425-16689-9 (paperback)/ISBN0-399-14383-1 (hardcover)/ISBN0-613-28967-6 (School & Library Binding).

- Carter, Howard and Arthur C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Courier Dover Publications, 1 June 1977, ISBN0-486-23500-9 The semi-popular account of the discovery and opening of the tomb written by the archaeologist responsible.

- Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane. Sarwat Okasha (Preface), Tutankhamun: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1963, ISBN0-8212-0151-4 (1976 reprint, hardcover) /ISBN0-14-011665-6 (1990 reprint, paperback).

- Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, The Mummy of Tutankhamun: The CT Scan Report, as printed in Ancient Egypt, June/July 2005.

- Haag, Michael. The Rough Guide to Tutankhamun: The King: The Treasure: The Dynasty. London 2005. ISBN1-84353-554-8.

- Hoving, Thomas. The Search for Tutankhamun: The Untold Story of Adventure and Intrigue Surrounding the Greatest Modern archeological find. New York: Simon & Schuster, 15 October 1978, ISBN0-671-24305-5 (hardcover)/ISBN0-8154-1186-3 (paperback) This book details a number of anecdotes about the discovery and excavation of the tomb.

- James, T. G. H. Tutankhamun. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, 1 September 2000, ISBN1-58663-032-6 (hardcover) A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of the funerary furnishings of Tutankhamun, and related objects.

- Neubert, Otto. Tutankhamun and the Valley of the Kings. London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1972, ISBN0-583-12141-1 (paperback) First hand account of the discovery of the Tomb.

- Rossi, Renzo. Tutankhamun. Cincinnati (Ohio) 2007 ISBN978-0-7153-2763-0, a work all illustrated and coloured.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tutankhamun. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treasure of Tutankhamun. |

| Library resources about Tutankhamun |

- Grim secrets of Pharaoh's city—BBC News

- 'Swiss geneticists examine Tutankhamun's genetic profile' by Reuters

- Ultimate Tut Documentary produced by the PBS Series Secrets of the Dead

British Museum Exhibitions

Exhibitions of artifacts from the tomb of Tutankhamun have been held at museums in several countries, notably the United Kingdom, Soviet Union, United States, Canada, Japan, and France.

The artifacts had sparked widespread interest in ancient Egypt when they were discovered between 1922 and 1927, but most of them remained in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo until the 1960s, when they were first exhibited outside of Egypt.[1] Because of these exhibitions, relics from the tomb of Tutankhamun are among the most travelled artifacts in the world. Probably the best-known tour was the Treasures of Tutankhamun from 1972 until 1981.

Other exhibitions have included Tutankhamun Treasures in 1961 and 1967, Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter beginning in 2004, Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs beginning in 2005, and Tutankhamun: The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs in 2008. Permanent exhibitions include the Tutankhamun Exhibition in Dorchester, United Kingdom, which contains replicas of many artifacts.

- 2TutTreasures (1961–67)

- 3The Treasures of Tutankhamun (1972–1981)

- 4Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs (2004-2011)

- 7Exhibitions of replicas

- 7.1Tutankhamun Exhibition, Dorchester

Ownership and normal display[edit]

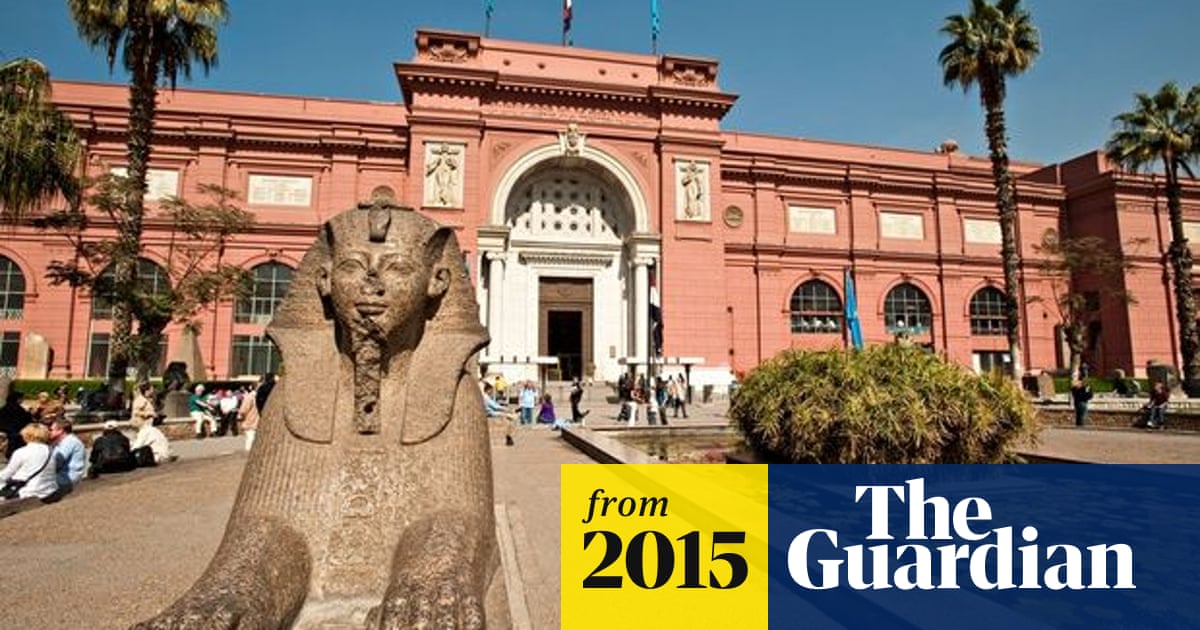

All of the artifacts exhumed from the Tutankhamun tomb are, by international convention, considered property of the Egyptian government.[2] Consequently, these pieces are normally kept at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo; the only way for them to be shown internationally is by approval of Egyptian authorities. Although journalists and government officials generally support the tours, some Egyptians argue that the artifacts should remain on display in their own country, where Egyptian school-children would have greater access to them, and where the museum's exhibit would attract foreign tourists.[3]

TutTreasures (1961–67)[edit]

The first travelling exhibition of a substantial number of Tutankhamun artifacts took place from 1961 to 1966. The exhibition, titled Tutankhamun Treasures, initially featured 34 smaller pieces made of gold, alabaster, glass, and similar materials.[4] The portions of the exhibition occurring in the United States were arranged by the Smithsonian Institution and organized by Dr. Froelich Rainey, Director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, with the assistance of Dr. Sarwat Okasha, Minister of Culture and National Guidance of the United Arab Republic.[4] The exhibit travelled to 18 cities in the United States and six in Canada.[3]

The exhibition had a public purpose in mind, to 'stimulate public interest in the UNESCO-sponsored salvage program for Nubian monuments threatened by the Aswan Dam project'.[4][5] The exhibition opened in November 1961 at the Smithsonian's National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C.[4]

Other museums to host the exhibition[edit]

The exhibition was shown in eighteen cities in the United States, and in six cities in Canada, including Montreal, and Ottawa.[3] Other stops on the tour included:

- University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania(December 15, 1961- January 14, 1962)[6]

- Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven, Connecticut (February 1–28, 1962)[5]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas (March 15, 1962- April 15, 1962)[6]

- Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska (May 1–31, 1962)[7]

- Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois (June 15 – July 15, 1962)[7]

- Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington (August 1, 1962- August 31, 1962)[6]

- California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, California (September 15, 1962- October 14, 1962)[6]

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California (October 30, 1962- November 30, 1962)[6]

- Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio (December 15, 1962- January 13, 1963)

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts (February 1–28, 1963)[6]

- City Art Museum of St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, (March 15- April 14, 1963)

- Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, Maryland, (May 1–31, 1963)

- Dayton Art Institute, Dayton, Ohio, (June 15- July 15, 1963)

- Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio, (September 15- October 15, 1963)

- Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Ontario (November 6-December 6, 1964)[8]

The exhibit was also part of 1964 World's Fair held in New York, United Arab Republic Pavilion (April 22 – October 18, 1964)

Japan (1965–1966)[edit]

From 1965 to 1966 an enlarged version of the 1961–1963 North America tour took place in Japan. The Japanese exhibition saw nearly 3 million visitors.[3]

- Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, Japan (August 21- October 1965)

- Kyoto, Japan (October–November 1965)

- Fukuoka Prefectural Culture Center, Fukuoka, Japan (December 1965– January 1966)

France (1967)[edit]

The French exhibit saw an attendance of 1,240,975 (It was titled Tutankhamun and His Time and had 45 pieces on display)

- Petit Palais, Paris, France (February 17 – September 4, 00000

The Treasures of Tutankhamun (1972–1981)[edit]

The genesis of the Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition reflected the changing dynamic of Middle-East relations.

United Kingdom[edit]

It was first shown in London at the British Museum in 1972. After a year of negotiations between Egypt and the United Kingdom, an agreement was signed in July 1971. Altogether, 50 pieces were chosen by the directors of the British Museum and the Cairo Museum to be shown at the exhibition, including 17 never before displayed outside Egypt. For insurance purposes, the items were valued at £9.06 million. In January 1972, they were transported to London on two civilian flights and one by the Royal Air Force, carrying, among other objects, the gold death mask of Tutankhamun. Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the exhibition on March 29, 1972. More than 30,000 people visited in its first week. By September, 800,000 had been to the exhibition, and its duration was extended by three months because of the popularity. When it did close on December 31, 1972, 1.6 million visitors had passed through the exhibition doors. All profits (£600,000) were donated to UNESCO for conserving the temples at Philae, Egypt.[9]

Treasures of Tutankhamun was the most popular exhibition in the museum's history.[10] It is considered a landmark achievement in Egypt–United Kingdom relations.[9] The exhibition moved on to other countries, including the USSR, US, Canada, and West Germany.

United States[edit]

Egyptian cultural officials initially stalled prospects of an American tour, as Egypt was then more closely aligned with the Soviet Union, where fifty pieces had toured in 1973.[1] However, relations thawed later that year when the U.S. interceded on Egypt's behalf to prevent the total destruction of Egypt's Third Army during a military conflict with Israel.[1] U.S. president Richard Nixon thereafter visited Egypt, becoming the first American President to do so since the Second World War, and personally prevailed upon Egyptian president Anwar Sadat to permit the artifacts to tour the United States – with the U.S. tour including one more city than the Soviet tour had included, and several additional pieces.[1] The showing was the largest of Tutankhamun's artifacts, with 53 pieces.[3]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art organized the U.S. exhibition, which ran from November 17, 1976, through September 30, 1979. More than eight million attended.[11] The Metropolitan's exhibition was designed to recreate for visitors the drama of the 1922 discovery of the treasure-filled tomb. Included along with original objects excavated from the tomb were reprints from glass plate negatives in the Metropolitan’s collection of the expedition photographer Harry Burton's photographs documenting the excavation's discoveries step by step.[12] The Smithsonian described the exhibit as one of the initial 'blockbuster exhibits' which sparked the museum community's interest in such exhibitions.[13]

After the six U.S. tour locations were named, San Francisco citizens bombarded the Mayor's Office with inquiries as to why the tour was not coming there. As a result, museum trustees flew to Egypt to meet with the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, where they worked out a mutual agreement for a seventh stop. Profits after exhibition expenses resulted in $10+ million going to the Egyptian Museum for refurbishing.[14]

Other museums to host the exhibition[edit]

After the exhibition left London in 1972, it toured the USSR from 1973–1975.

- Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow (December 1973– May 1974)

- Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg (July 1974– November 1974)

- National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kiev (January 1975– March 1975)

During the years 1976 to 1979 the exhibition was shown in the United States. While at the following venues, the exhibit attracted more than eight million visitors: (NGA)

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (November 17, 1976 – March 15, 1977) – 836,000 visitors in over 117 days[13]

- Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois (April 14 – August 15, 1977)

- New Orleans Museum of Art (September 15, 1977 – January 15, 1978)

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art (February 15 – June 15, 1978)

- Seattle Art Museum (July 15 – November 15, 1978)[15]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City (December 15, 1978 – April 15, 1979)

- M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco, California (June 11 – September 30, 1979)

Tutankhamun Exhibition 2019

After the exhibit left the U.S. it went to:

- Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (November 1 – December 31, 1979)

- Egyptian Museum of Berlin, Berlin, West Germany (February 16 – May 26, 1980)

- Kölnisches Stadtmuseum, Cologne, West Germany (June 21 – October 19, 1980)

- Haus der Kunst, Munich, West Germany (November 22 – February 1, 1981)

- Kestner-Museum, Hanover, West Germany (February 20 – April 26, 1981)

- Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, West Germany (May 15 – July 19, 1981)

While the exhibition was on display in San Francisco, Police Lieutenant George E. LaBrash suffered a minor stroke as he guarded the treasures after hours. He later filed a lawsuit against the city on the theory that his injury had resulted from the legendary curse of the pharaohs.[16]

Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs (2004-2011)[edit]

Originally entitled Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter, this exhibition is made up of fifty artifacts from Tutenkhamun's tomb as well as seventy funerary goods from other 18th Dynasty tombs. The tour of the exhibition began in 2004 in Basel, Switzerland and went to Bonn, Germany on the second leg. The European tour was organized by the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), and the Egyptian Museum in cooperation with the Antikenmuseum Basel and Sammlung Ludwig. Deutsche Telekom sponsored the Bonn exhibition.[17]

Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs consists of the same items from the Germany and Switzerland tour but in a slightly different exhibition. Of the 50 artifacts from the Tutankhamun tomb fewer than ten were repeated from the 1970s exhibition. This exhibition began in 2005, and was directed by Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, together with Arts and Exhibitions International and the National Geographic Society.[18]

Exhibition overview[edit]

The initial American leg of the Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs exhibition attracted estimated three million visitors, and was displayed in the following venues:

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art – June 16 to November 15, 2005

- Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale – December 15, 2005 to April 23, 2006

- Field Museum of Natural History – May 26, 2006 to January 1, 2007

- Franklin Institute – February 3 to September 30, 2007

From November 15, 2007, to August 31, 2008, the exhibition was shown in The O2, London. It then stayed for eight months in Dallas, Texas, at the Dallas Museum of Art (October 2008 – May 2009), and for nine months at the De Young Museum in San Francisco from June 27, 2009 to March 28, 2010. From April 23, 2010, to January 11, 2011, the exhibition was shown at the Discovery Times Square Exposition in New York City.

In 2011 the exhibition visited Australia for the first time, opening at the Melbourne Museum in April for its only Australian stop where it achieved the highest touring exhibition box office numbers in the country's history before Egypt's treasures return to Cairo in December 2011.[19][20][21]

Artifacts on display[edit]

Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs displays actual items excavated from tombs of ancient Egyptian Pharaohs. From 130 authentic artifacts presented, 50 were found specifically during the excavations of Tutankhamun's tomb. The exhibition includes 80 exhibits from the reigns of Tutankhamun's immediate predecessors in the Eighteenth dynasty, such as Hatshepsut, whose trade policies greatly increased the wealth of that dynasty and enabled the lavish wealth of Tutankhamun's burial artifacts. Download mini tools partition wizard 7 full version. Other items were taken from other royal graves of the 18th Dynasty (dating 1555 BCE to 1305 BCE) spanning Pharaohs Amenhotep II, Amenhotep III and Thutmose IV, among others. Items from the largely intact tomb of Yuya and Tjuyu (King Tut's great-grandparents; the parents of Tiye who was the Great Royal Wife of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III) are also included. Yuya and Tjuyu's tomb was one of the most celebrated historical finds in the Valley of the Kings until Howard Carter's discovery in 1922. This exhibition does not include either the gold death mask that was a popular exhibit from The Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition, or the mummy itself. The Egyptian Government has determined that these artifacts are too fragile to withstand travel, and thus they will permanently remain in Egypt.[22] The mummy of Tutankhamun is the only known mummy in the Valley Of The Kings to still lie in its original tomb, KV62.

History[edit]

Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs was expected to draw more than three million people.[18] The exhibition started in Los Angeles, California, then moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Chicago and Philadelphia. The exhibition then moved to London[23] before finally returning to Egypt in August 2008. Subsequent events have propelled an encore of the exhibition in the United States, beginning with the Dallas Museum of Art in October 2008 which hosted the exhibition until May 2009.[24] The tour continued to other U.S. cities.[25] After Dallas the exhibition moved to the de Young Museum in San Francisco, to be followed by the Discovery Times Square Exposition in New York City.[26]

Tutankhamun: The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs (2008-2013)[edit]

Tutankhamun British Museum 2019 Schedule

This exhibition, featuring completely different artifacts to those in Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs, first ran at the Ethnological Museum in Vienna from March 9 to September 28, 2008 under the title Tutankhamun and the World of the Pharaohs. It featured a further 140 treasures from the Valley of the Kings including objects from the tomb of King Tut. The exhibition continued with the following itinerary:

- Atlanta Civic Center (November 15, 2008 to May 22, 2009), Atlanta, Georgia

- Indianapolis Children's Museum (June 25 to October 25, 2009), Indianapolis, Indiana

- Art Gallery of Ontario (November 20, 2009 to May 2, 2010), Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- Denver Art Museum (July 1, 2010 to January 2, 2011), Denver, Colorado

- Science Museum of Minnesota (February 18 to September 5, 2011), St Paul, Minnesota

- The Museum of Fine Arts (October 13, 2011 to April 15, 2012), Houston, Texas

- Pacific Science Center (May 24, 2012 to January 6, 2013), Seattle, Washington[27]

Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh (2018-2021)[edit]

This exhibition features over 150 authentic tomb objects, with many appearing outside of Egypt for the first and last time. Running from March 2018 to May 2020 touring America, France and England. A new permanent exhibition for the treasures is being constructed at the Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo so this is the last time the contents of the tomb will be displayed outside of Egypt.

- California Science Center (March 24th 2018, to January 6th, 2019), LA, California[28]

- Grande halle de la Villette (March 23rd 2019 to September 15th 2019), Paris, France[29]

- Saatchi Gallery (November 2nd 2019 to May 3rd, 2020), London, England[30]

- Australian Museum (6 months, 2021), Sydney, Australia[31]

Exhibitions of replicas[edit]

Several exhibitions have been established which feature replicas of Tutankhamun artifacts, rather than real artifacts from archaeological sites.[3] These provide access to pieces of comparable appearance to viewers living in places where the real artifacts have not circulated. The first replica exhibition, a copy of the entire tomb of Tutankhamun, was built only a few years after the discovery of the tomb. This replica was temporary, staged by Arthur Weigall for the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, in 1924.[3] Modern replica exhibitions exist in Dorchester, Dorset, England, in Las Vegas, Nevada, United States, and even in Cairo, Egypt (where the replica exhibition is intended to reduce the overwhelming traffic to the real locations).[3] A travelling exhibition of replicas titled Tutankhamun: His Tomb and Treasures, featuring several hundred pieces, has been shown in Zürich, Brno, Munich, and Barcelona.[3]

Tutankhamun Exhibition, Dorchester[edit]

The Tutankhamun Exhibition in Dorchester, Dorset, England, is a permanent exhibition set up in 1986 by Michael Ridley as a re-creation of the tomb of the ancient Egyptian PharaohTutankhamun. The exhibition does not display any of the actual treasures of Tutankhamun, but all artifacts are recreated to be exact facsimiles of the actual items. Original materials have been used where possible, including gold. The story line is based around the famous English archaeologist Howard Carter. The Exhibition reveals history from Carter's point of view as he entered the tomb in Valley of the Kings in November 1922.

Exhibition sections[edit]

- The entry section of the Exhibition displays general information about Tutankhamun's life and death.

- Tutankhamun's mummy. A life-size model of the mummy is displayed. The exhibitors claim that it took more than two years to recreate the mummy. X-ray pictures taken from the real mummy helped to make an exact copy.

- The ante-chamber contains replicas of furniture and Tutankhamun's personal items he had been buried with.

- The burial chamber exhibits replicas of the sarcophagus and coffin of Tutankhamun.

- The Treasure Hall shows recreations of statues and jewels found within the tomb of Tutankhamun. Sitting statue of Anubis, the Golden Throne, Gold Death Mask and statue of guardian goddess Selkit are displayed among other items.

Discovering Tutankhamun Exhibition, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford[edit]

The Discovering Tutankhamun exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England, was a temporary exhibition, open from July until November 2014, exploring Howard Carter’s excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922. Original records, drawings and photographs from the Griffith Institute are on display.[32] The complete records of the ten year excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun were deposited in the Griffith Institute Archive at the University of Oxford shortly after Carter's death.[33] A replica death mask was displayed along with replicas of other items from the tomb.

References[edit]

- ^ abcdMelani McAlister, Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and U.S. Interests in the Middle East Since 1945 (2005), p. 127.

- ^Zahi A. Hawass, The Golden Age of Tutankhamun: Divine Might and Splendor in the New Kingdom (2004), p. 130.

- ^ abcdefghiMalek, Jaromir (January 31, 2009). 'Some thoughts inspired by a current exhibition:'Tutankhamun: His Tomb and Treasures''. Brno, Czech Rep.

- ^ abcd'Tutankhamun Treasures', Art international: Volume 6 (1962), p. 51.

- ^ abInstitute of International Education, Overseas: Volume 1 (1961), p. 31.

- ^ abcdefSmithsonian Institution, Tutankhamun Treasures: A Loan Exhibition from the Department of Antiquities of the United Arab Republic (1961).

- ^ abMidwest Museums Conference, Midwest Museums Quarterly: Volumes 21–28 (1961), p.34.

- ^'Golden glints from the past'. The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. October 31, 1964. p. 15.

- ^ abZaki, Asaad A. (2017). Tutankhamun Exhibition at the British Museum in 1972: A historical perspective. The 3rd International Conference on Tourism: Theory, Current Issues and Research – April 27-29, 2017, Rome, Italy.

- ^'Treasures of Tutankhamun'. The British Museum. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^Peter Green, Classical Bearings: Interpreting Ancient History and Culture (1998), p. 77.

- ^Finding aid for the Irvine MacManus records related to 'Treasures of Tutankhamun' exhibition, 1975-1979 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

- ^ ab'Audience Building: Marketing Art Museums'(PDF). Smithsonian Institution. October 2001.

- ^Silverman, Harold I., ed. (1979). The Treasures of Tutankhamun in San Francisco. California Living Books. p. 32. ISBN0-89395-014-9.

- ^'Tut Lecture Set'. The Spokesman Review. March 24, 1978.

- ^'Chatter', People Magazine, Vol. 17, No. 4 (February 1, 1982).

- ^'Under Tut's spell'. Al-Ahram Weekly. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ ab'King Tut exhibition. Tutankhamun & the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. Treasures from the Valley of the Kings'. Arts and Exhibitions International. Retrieved August 5, 2006.

- ^'Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs'. Kingtutmelbourne.com.au. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^'Melbourne Museum: Tutankhamun'. Museumvictoria.com.au. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^'Tutankhamun exhibition smashes box office record'. ABC News. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ^Jenny Booth (January 6, 2005). 'CT scan may solve Tutankhamun death riddle'. The Times. UK.

- ^Return of the King (Times Online)Archived June 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^'Dallas Museum of Art Website'. Dallasmuseumofart.org. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^Associated Press, 'Tut Exhibit to Return to US Next Year' Archived October 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^'Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs, King Tut Returns to San Francisco, June 27, 2009 – March 28, 2010'. Famsf.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^'Tutankhamun: The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs'. kingtut.org. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^'King Tut: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh'. kingtutexhibition.com. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^'Toutânkhamon, le Trésor du Pharaon'. expo-toutankhamon.fr. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^'Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh'. tutankhamun-london.com. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^'Sydney to host largest Tutankhamun exhibition to ever leave Egypt'. smh.com.au. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^'Ashmolean Museum'. Ashmolean website. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^'Griffith Institute Archive'. Griffith Institute Archive. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- NGA – Treasures of Tutankhamun

External links[edit]

- A digital display of Tutankhamun primary sources and artifacts at the Griffith Institute at Oxford University.

Blog

- Download Red Alert 2 Full Version Gratis

- Nostalgic Meiko San Mix Mp3

- Lagu Dangdut Elvy Sukaesih

- Dc Unlocker 2 Device Download

- Causes Of Flat Battery

- Download Table Planning Software

- Amd Overdrive Stability Test

- Torrent Pacifist 3.6.1 (mac)

- How To Install Mods Into Sims 4

- Install Wow Addons Without Curse

- Companeros Viento Kiarostami Descargar

- Descargar Discografia De Tito Nieves 320 Kbps

- Vivitar Ipc 113 Manual

- Xcom 2 Character Pool Download

- Download Plant Vs Zombie 2 Pc Full

- Cara Instal Windows 10

- Battlefield Bad Company 2 Vietnam Download

- Video Sound Effects Name

- Ynw Melly Till The End Mp3

- Morph Image Onlin On Curve